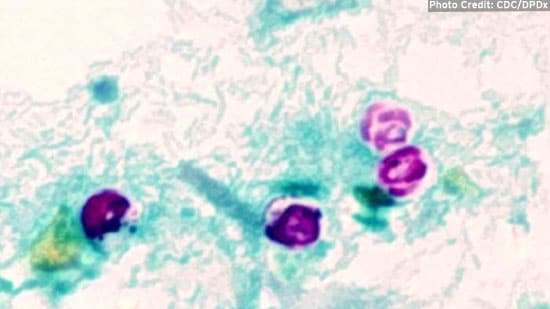

Cryptosporidium

What is Cryptosporidium?

Cryptosporidium is recognized as one of the most common causes of waterborne disease among humans in the United States. The parasite may be found in every region of the United States and throughout the world.

Cryptosporidium species are obligate intracellular parasites that are primarily found in cattle, but have also been detected in other animals. Several Cryptosporidium species can infect humans via contact with infected fecal material. The parasites are protected by outer shells that allow them to survive outside the body for long periods of time. They are resistant to most chemical disinfectants, but are susceptible to drying and the ultraviolet portion of sunlight.

A significant outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in 1993 in Milwaukee resulted in diarrheal illness in an estimated 403,000 persons; this was ultimately linked to contaminated drinking water.1 Other water-related outbreaks have been attributed to swimming pools and amusement park wave pools or water rides.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS?

The primary symptom of cryptosporidiosis in most healthy individuals is voluminous watery diarrhea for a mean duration of 12 days, which begins up to a week after exposure. Other symptoms can include dehydration, weight loss, stomach cramps or pain, fever, nausea or vomiting. Some infected people have no symptoms at all. Studies in healthy immunocompetent individuals have shown that the dose that causes illness in 50 percent of the subjects is between 10 and 1000 oocysts, dependent on the particular strain.2

HOW IS IT TRANSMITTED?

Cryptosporidium is found in soil, food, water or surfaces that have been contaminated with feces, since oocysts are shed by the infected individual. Cryptosporidium could occur, theoretically, on any food touched by a contaminated food handler, although no foodborne outbreaks have been reported. For example, the incidence of infection due to Cryptosporidium is higher in child day care centers that serve food. Fertilizing salad vegetables with manure is another possible source of human infection. Large outbreaks have been associated with contaminated water supplies.

HOW IS IT CONTROLLED?

Key for control of Cryptosporidium is control of the water supply, including untreated water from shallow wells, lakes, rivers, springs, ponds, streams or any recreational water. Water can be treated via heating to a rolling boil for at least one minute or filtering through a filter that has an absolute pore size of at least one micron or has been NSF rated for "cyst removal."

Because it has a thick outer shell, this particular parasite is highly resistant to disinfectants such as chlorine and iodine. Freezing has been found to inactivate some proportion of oocysts, but it may take an extended time,3 and the effect of freeze-thaws needs to be considered. Other controls include effective handwashing and excluding ill individuals from handling food.

For assistance with this topic or other food safety questions for your operation, please Contact Us.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER INFORMATION

- FDA

- CDC

- WHO

- FAO

- EPA - Infective dose (92 KB)

- Erickson, M.C. and Ortega, Y. R. 2006. Inactivation of Protozoan Parasites in Food, Water and Environmental Systems. Journal of Food Protection. 69(11): 2786-2808.

- Institute of Food Science & Technology "Cryptosporidium"

1Cryptosporidium Infections Associated with Swimming Pools

2Dupont, H.L., Chappell, C.L., Sterling, C.R., Okhuysen, P.C., Rose, J.B. and Jakubowski, W. 1995. The infectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum in healthy volunteers. New Engl. J. Med. 332:855-859.

3Effects of freeze–thaw events on the viability of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in soil